You’ve been planning for retirement for a long time. By your calculations, the money you’ve accumulated should be more than enough to live the retirement lifestyle you’ve dreamed about no matter how long you live. You’ve taken into account taxes, inflation, healthcare, and the cost of all the things on your bucket list. To pay for it all you’ll withdraw the same percentage from your portfolio every year. It sounds like the perfect plan. But did you account for perhaps the biggest portfolio-killer, the one thing that could destroy all those years of planning and saving, the financial goblin known as — Sequence of Returns?

It seems simple. If you average a 6% return in your portfolio, you can withdraw 6% every year and not have to worry about running out of money. It sounds simple and if markets gave you 6% each and every year, it would be. But that isn’t how markets work and the volatility of returns as well as the sequence of returns matters a great deal for retirees.

If your retirement starts with a series of negative returns, even small ones, the impact can carry on for the rest of your retirement. In an extreme case, it could mean the difference between a comfortable retirement and surviving on Social Security. Here’s a real-world example to illustrate the risk.

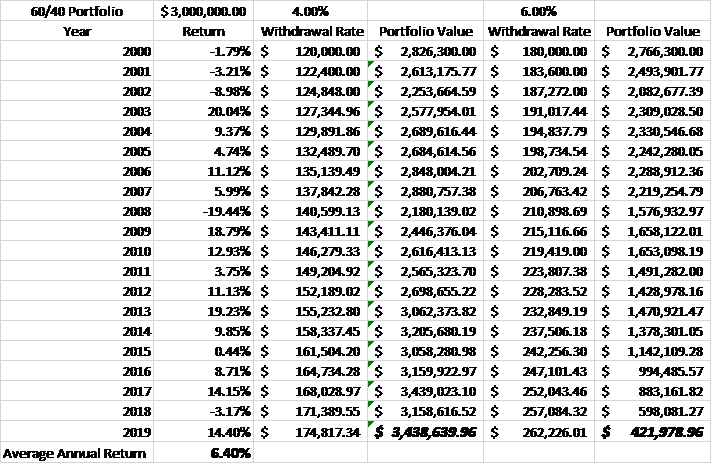

Initial Conditions

- $3,000,000 initial portfolio.

- Assume retirement in the year 2000.

- Portfolio is a standard 60/40 portfolio with 60% stocks and 40% bonds.

- Returns are actual returns of this 60/40 portfolio from 2000 through 2019 (60% Vanguard Total Stock, 40% Vanguard Total Bond).

- We compare two initial withdrawal rates of 4% and 6%. The amount withdrawn rises by 2%/year to account for inflation.

In this case, the 4% withdrawal rate is obviously sustainable and the account value continues to grow. With the 6% withdrawal rate, even though it is less than the average annual return, the balance declines and would soon hit zero. In fact, if you change the withdrawal rate to 6.3%, the balance falls below zero in 2019.

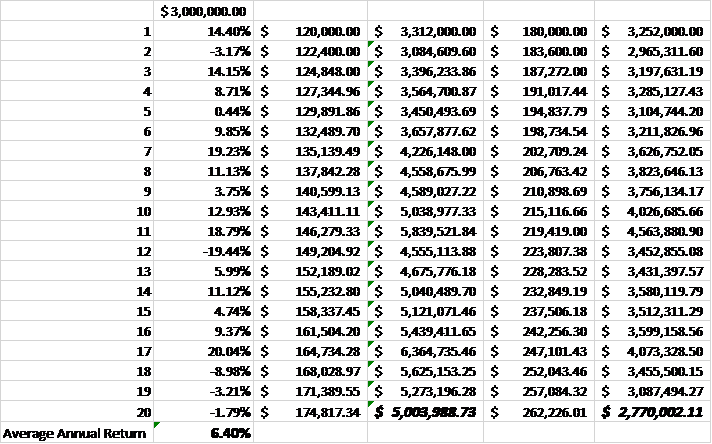

Now let’s look at what happens if we reverse the returns. Let’s have the illustration start with the return for 2019 and work backward. Instead of starting with three straight years of negative returns, 2 of the first three years produce double-digit returns.

Merely switching the sequence of returns produces a vastly different result. The average annual return is exactly the same but the ending balances are very different.

Future returns are unlikely to match those of the past. The reason is simple. The 10-year Treasury note yielded nearly 7% in 2000 while today it yields just 1.75%. Mathematically, bonds cannot provide the returns they have in the past. Unless stocks return much higher than average returns in the future, a balanced 60%/40% stock/bond portfolio cannot produce returns near historic levels. We don’t think it is prudent to plan for higher-than-average returns.

Of course, this is just an example. The reality is, here at Alhambra, we review withdrawal rates regularly and advise when they need to be changed. We do think it’s important though to start with a conservative rate, especially after markets have had a good run as they have now. If the initial withdrawal rate proves too conservative, it can always be changed in the future. We just don’t want to start in a hole.